2013 • 5 • 2

All four of us stood by the door of the museum, waiting for the caretaker.

“If the whole island had been declared leprosy-free,” I couldn’t help but scratch the back of my head in confusion, “where are the former patients now?”

“Most of them have gone back to the outside world,” answered Kuya Toto, a local and one of our tour guides. “Some stayed.”

“But I don’t understand,” I expressed my inability to process information efficiently. “Who are living here now?”

“Some just moved here from other places. Toto is from Metro Manila but he decided to work here,” Jona replied with a smile. She, too, is a local, touring us around. “The others are descendants of the patients. I am a descendant.” There was long aaaaaah heard. It was me signifying that the information had been processed finally.

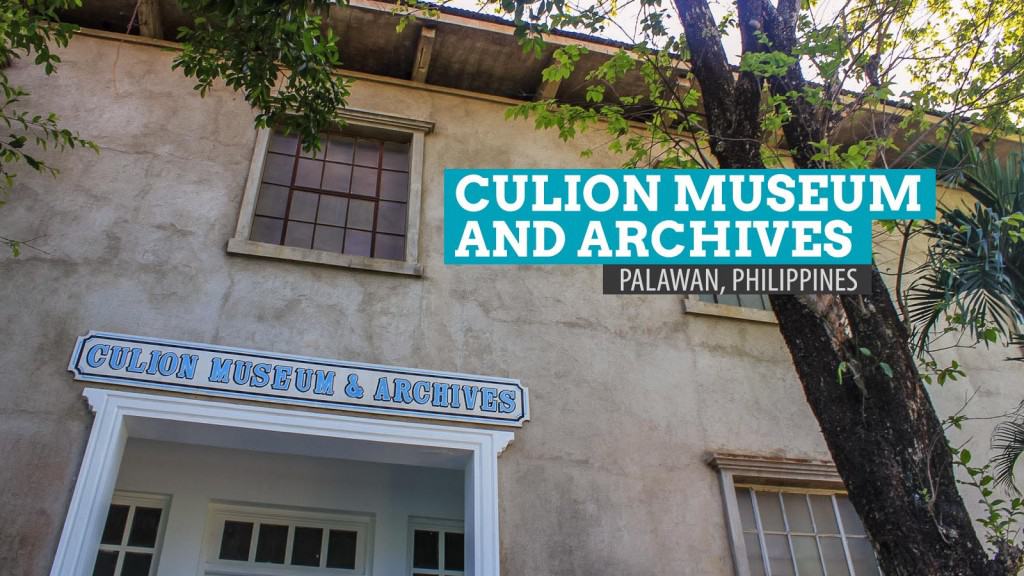

Located inside the compound of the town’s hospital and sanitarium, the Culion Museum and Archives houses the most detailed and significant information about the establishment of the leprosarium in the island in 1906 up to the development of the cure, the multi-drug therapy, in the 1980s.

The history of Culion as a leper colony can be traced back to May 27, 1906, when Coast Guard cutters Polillo and Mindanao docked along the shore of Culion and carried 370 Hansenites (lepers) from Cebu. Most of them were brought here against their will. Some of them would later embrace a life of normalcy in this town, specifically designed for their betterment and the search for better treatments. Many of the devices, medicines, and even the mundane items that patients and health workers used are on display, providing a glimpse to the milestones and setbacks of Culion as a sanctuary for what many used to dub the “living dead.”

The museum building has two stories, both open to the public. The artifacts on the ground floor narrates the history of the island, describes the lifestyle of the patients, and explains the disease in great detail. Here are some of the most interesting items inside.

The upper level highlights a memorial honoring the brave men and women — physicians, nurses, pharmacists, priests, pastors, and technicians — who “had answered the call of duty and had served the leprosy patients with utmost love, dedication, and care.”

When we came full circle, a sign that the tour inside the museum had ended, I could not help but feel thankful for this opportunity. Within the best of my ability, I tried to understand leprosy and the life that sprung out here, although by force in the beginning. The most memorable part of the tour was when my friend Mica spotted a photo of his great grandfather, one of the major movers in the field of leprology, posted on the wall. His contributions to the quest for the cure was honored. It was the reason we made a trip to this unusually fascinating town.

And right at that moment, I realized that all of us represent a certain sector of the modern society of Culion. There was my friend Mica, a descendant of a doctor who helped find the cure to the illness; Jona, a descendant of a leprosy patient who chose to stay; Kuya Toto, an outsider who moved to Culion recently to live there permanently; and then there was me, a tourist.

Well, I’m not a descendant of anyone relevant but I was there to learn about the island and its constant struggle through the decades. The days of the island being a leper colony are gone and a new era is coming — Culion as a tourist destination. And while thousands of islands in the country are blessed with natural beauty, Culion has a compelling story to tell. And it’s one that needs to be heard.

How to get here: Fly to Busuanga and at the airport, take a van/shuttle to the town center of Coron (P150). At Coron Pier, catch the 1:30pm boat going to Culion (P180). There’s only one boat per day so don’t miss it. From Culion port, take a tricycle to the museum. Alternatively, you may join a Culion Tour, offered by hotels and tour operators in Coron (P1200 per person).