2013 • 4 • 3

That scene alone sums up the park. Three zebras escaping the scorching sun took shelter in a garage and there they stayed beside a rusty, old Pinoy jeepney. It was an intriguing sight, a harbinger of how I would see the place after spending half a day in it.

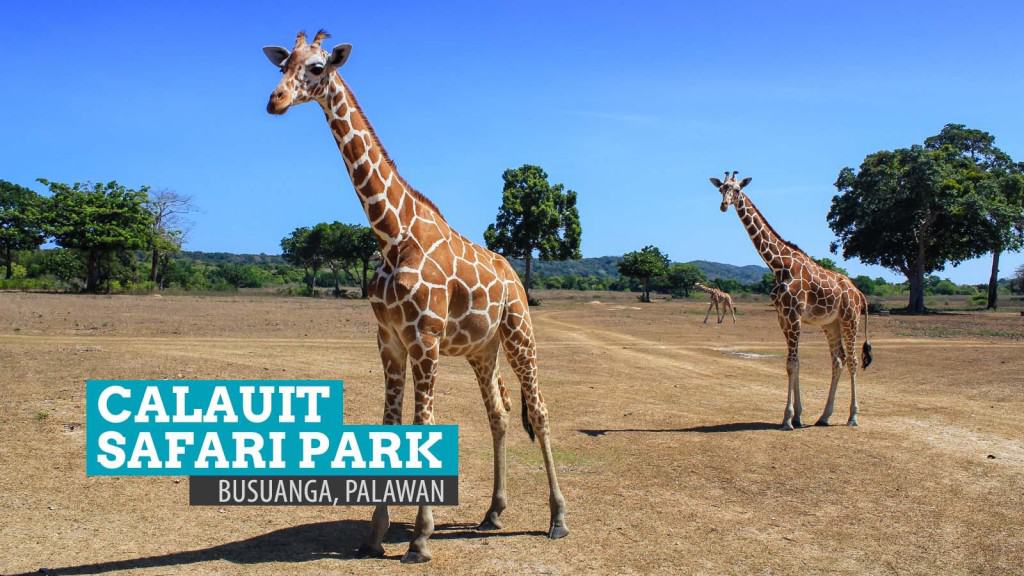

The land rover we were riding stirred dust across a vast plain where giraffes roamed gracefully, hopping from tree to tree. Zebras bent their necks as they grazed, pulling the grass off the more moist corners of the island. Africa, I mumbled as our vehicle slowed down to halt. A far cry, maybe, but for now this was the closest I could get to an African safari — Calauit Safari Park.

We climbed down to the arid ground and Kuya Florante, a caretaker and tour guide, led us under the shade of a gazebo. Four giraffes, I counted. They, too, were avoiding the sun and were oblivious to our presence, which until then was thought to be irresistible (wahaha). “They look small,” my friend Mica remarked while looking at them from afar. But that would change as soon as they came closer and dwarfed us. It was the first time that I got this close to the tallest land animal in the world, and it felt like I would break my neck any time as I kept looking up to their cute, gentle faces.

“This is Isabel,” said Kuya Florante while rubbing the neck of the biggest giraffe of the lot. The others, he introduced as Miller, Terrence, and Mylene. “We usually name them after their sponsors,” he answered when asked how they come up with the names.

Feeding the giraffe is allowed here. Our group tried it. I tried it too, thinking that there was nothing wrong with it. But now that I’m writing about it and after reading about the behavior of these animals and their relationship with the human inhabitants of Calauit, I figured I probably did a bad thing. Maybe it would be best for them to not be get used to humans and for tourists to minimize impact. Maybe feeding them isn’t a good idea after all. The park may be big enough for these animals but it has faced one problem after another through the years.

Calauit Safari Park covers almost 3800 hectares. Formerly known as Calauit Game Preserve and Wildlife Sanctuary, the park was established on August 21, 1976 by Presidential Proclamation 1578 issued by President Ferdinand Marcos.

You might be wondering: How did the giraffes and zebras get here? That’s easy to answer — by boat. One hundred and four animals which also included six types of antelopes (impala, gazelle, bushbuck, eland, waterbuck, and tobi) were brought here from Kenya. The green island was transformed to a savannah — its residents relocated and its bamboo forests cleared to provide a suitable environment for the animals.

The more interesting question is: Why? The most common reason you’re gonna hear is that this was a conservation effort by President Marcos. It is said that when he attended a summit meeting in the African state, the Kenyan government asked the International Union for Conservation of Nature for assistance in the conservation of their wildlife. Calauit was Marcos’s answer to the call.

Of course, some do not find this too convincing. An Inquirer report in 2011 revealed something else: Marcos wanted to launch a tourism business. Tony Parkinson, a British man who organized the translocation of animals from Kenya to the Philippines, said, “None of them were endangered… that was all nonsense. We would never have put them on an island like that if they were endangered.” Which one to believe is up to you.

Today, according to Kuya Florante, there are 23 giraffes, 38 zebras, and around 1000 Calamian deer on the island today. The antelopes have all died out. The Calamian deer is endemic to Palawan and is an endangered species but their population has improved in the park. The male Calamian deer is horned; we only spotted one male of the dozens we have seen that morning.

While most animals are free to run around and explore the island, there are those that are in captivity. Among these are four Philippine crocodiles, three porcupines, two pythons, a civet cat, a wild boar, a sea gull, and a number of tortoises. But the giraffes and zebras remain the crowd favorites among all animals in the sanctuary.

The environment (natural, social, and even political) has changed since Marcos created Little Africa in Calauit and time does not prove to be friendly to the park, which is facing a number of challenges today. Budget cuts have pushed the number of workers to dwindle from 300 to 30. The former inhabitants of the peninsula who were relocated decades ago are returning via the Balik-Calauit movement. And the animals are reported to have been on one end of a conflict with the residents.

Whatever the real intentions are, one thing that remains the same is that the animals are already here. We brought them here. We adopted them. “All the animals here are Filipinos now,” Kuya Florante shared, explaining that the original individuals imported from Africa are all dead, leaving behind the offsprings, which are all born in Calauit. The least we could do is take care of them.

How to get here: From Manila, fly to Busuanga airport. If your hotel is in Coron, you can take a van/shuttle to Coron town. Here, there are several options available. You may join a group tour offered by travel agencies, normally around P2500-3000 per head. If you’re a big group, you may charter a private boat to Calauit (which can also take you to other gorgeous islands including Black Island) for P9300 for 1-4 pax or P10,400 for 5-8 pax.

Calauit Entrance Fee: P200 for Filipinos, P400 for foreigners

Use of land rover: P1000 (divided by how many you are in the group)